Reading Photographs

Tom MortonGuest Contributor, BC Heritage Fairs Society.

Tom Morton is the former coordinator of the BC Heritage Fairs and still serves as a director. He taught at the high school and university levels for more than 30 years in Kabala (Sierra Leone), Montreal and Vancouver. He is the author of numerous articles and books on education. Tom has received the British Columbia Social Studies Teacher of the Year Award, the Governor General’s History Award for Excellence in Teaching and the Kron Award for Excellence in Holocaust Education.

Why did you want to become a history teacher?

As a child I was curious about stories: how my mum came here alone on a free train ticket from Winnipeg; why there was a gas mask in our attic. As an adult I love a good story but I also like to peel back the cover to see how the story was constructed.

How did you become a history teacher?

Certainly through course work and teacher training, but mostly through on-the-job learning. There is a saying that one learns history by doing history—formulating questions, looking at evidence and the like. I became a history teacher by doing history teaching—preparing lesson content and teaching strategies, studying student responses, planning with colleagues and more of the countless things that teachers do.

What got you interested in using historical photographs?

I had good teachers. Charlie Hou first sparked my interest in using paintings such as The Death of Wolfe to understand history. Above all he taught me the appeal of political cartoons for students and the cartoonists’ varied devices. Walt Werner and Jane Card taught me about the power of visual sources and the many ways we can read photographs.

What is the most important thing to find out when using a photograph to tell a story about the past?

This will depend on the questions we ask. The first question is usually “What is it?” A documentary photo, for example, is very different from a family photo or a daguerreotype. Other questions would be about the photographer: “How has the photographer organized the photo? What impression was he or she trying to create? Who did he or she leave out of the photo?” A third set of questions would be “How was this photograph used? How did the audience interpret it?” To answer these we need to understand the historical context and study the photo closely.

What have you learned from working with photographs?

They are everywhere so it is worth paying attention to them. The fleeting, fast moving photos on the web are entertaining but good historical photos can have both interesting content and an emotional oomph that can create curiosity about the past. Some are the only sources of the lives of people who did not leave written records.

Many people, however, tend to read historical photographs at face value as true pictures of the past. They are not. They were created by individuals in a particular context and often carefully constructed. They take patience, puzzlement, and knowledge of the context to understand them fully. When we do so, we can often find hidden stories that enrich our understanding.

Stories by or about this person

Offered here are some suggestions on how to encourage and guide your students when they are using historical photographs.

Thinking about using historical photographs in your classroom? If you need some tips to help you plan, look no further.

Read this article by educator Tom Morton for some useful guiding questions to ask yourself when you are looking at historical photographs.

Try this worksheet to help you think through what you see when you first look at a historical photograph.

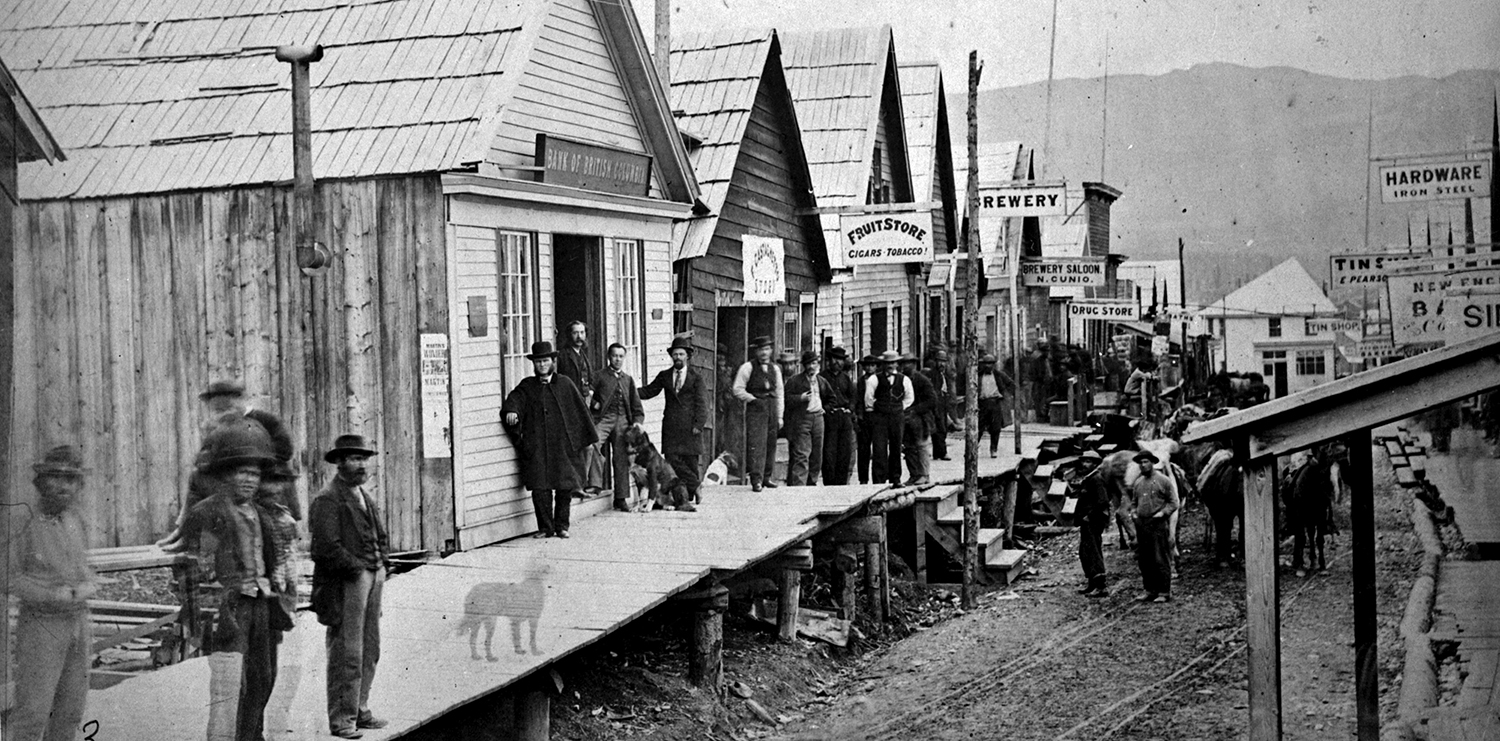

Photographer Fredrick Dally’s story is highlighted to give you more insight into his images of BC’s Gold Rush.

What stories of the Cariboo Gold Rush do photos help to tell? Watch this short tutorial on how to take a photograph from simple face value to deeper inferences about the past.

Don BourdonCurator, Images & Paintings (Retired)

Why did you want to become a curator?

I decided to become a self-styled curator when I was ten years old (in 1966). I started my own human and natural history museum in celebration of one of BC’s many centennials—the union of the two crown colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. What a weird little kid! I loved the stories associated with objects and collections and I still do. Throughout my career as an archivist I have been able to curate exhibitions as the end products of acquisition, preventive conservation, arrangement and description, access and public programming.

How did you become a curator of images and paintings?

I have been fascinated with photography and images for most of my life. I studied history, archives administration and records management at the University of British Columbia and the University of Alberta. I have been privileged to work with hundreds of thousands of photographs in archival and museum collections, first as a volunteer at the North Vancouver Museum and Archives (1972–1980) and then as an archivist at the City of Vancouver Archives (1976–1980), the Glenbow Museum (1980–1983) and the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies (1983–2006). I joined the BC Archives in 2007 as manager of access services and moved to the curator position to resume my love affair with collections, context and sharing these fabulous resources with others. Every day I learn from the interconnectedness of collections and from my colleagues.

What do you do as a curator of images and paintings?

I have a great job! I investigate possible acquisitions and help bring them to fruition. I conduct research so that we can advance scholarship and share our discoveries with researchers, exhibition enthusiasts, students, the people of BC and our visitors from around the world. Much of my work involves putting people in touch with works of art and photographs so that they can make their own discoveries. My job is really about enabling others and I am constantly amazed by the points of view, knowledge and passion of the people who access our collections.